Analyst: Gandhi Created “Three-Tiered System” of Racial Segregation in South Africa

Admin | On 13, Oct 2018

Gandhi declared, “The white race of South Africa should be the predominating race”

BLANTYRE, Malawi: Oct. 13, 2018 — As citizens of Malawi are locked in a struggle to prevent installation of a statue of Mohandas “Mahatma” Gandhi in their second-largest city, new scholarship regarding Gandhi’s 21 years in South Africa continues to emerge.

“Gandhi fought for apartheid-style segregation laws in colonial South Africa,” explains Pieter Friedrich, an analyst of South Asian affairs. “His first action when he arrived in South Africa with a law degree from London was to demand installation of a third door in the post office in the city of Durban. It already had two doors — one for whites and the other for all non-whites. Instead of protesting segregation, Gandhi called it an indignity that Indians had to share a door with black Africans and successfully demanded a door for Indian use only.”

Friedrich, in a lecture delivered at Sacramento State University in California, analyzes a series of statements and actions by Gandhi in South Africa. “He was only 26 years old when he worked to racially segregate the Durban Post Office,” notes Friedrich. However, he reports that Gandhi was 34 years old in 1903 when he wrote a letter to the colonial British government declaring, “The white race of South Africa should be the predominating race.”

He continues: “Analysis of Gandhi’s 1925 autobiography and comparison to his contemporary writings 20 or 30 years earlier exposes direct contradictions which can only be explained as him lying about his actions in South Africa. Throughout his entire time in South Africa — not just for a short period, but for two decades — Gandhi repeatedly wrote about his contempt for black people and worked to create a three-tiered system of racial segregation to separate blacks from Indians. Gandhi vociferously protested against equality.”

He points to an 1895 petition to the colonial government which praises “Brahmanism,” the caste-based philosophy that holds the highest-caste Brahmans as supreme. Referring to Indians as children of the land which produced Brahmanism, Gandhi wrote that “one cannot but help regretting that the children of such a race should be treated as equals of the children of black heathendom and outer darkness.”

Friedrich explains that scholarship about Gandhi’s South African period was previously hindered by lack of information. “Gandhi’s unedited ‘Collected Works’ runs to 100 volumes. Compilation only began in 1960 — 12 years after Gandhi’s death — and wasn’t completed until 1999. Before it was digitized and made freely available as PDFs, researchers had to buy the massive set and flip through thousands of pages. Academics before the 21st century simply didn’t have access to any original source material. All they had was Gandhi’s self-promotional autobiography, or biographies like the first one written about him in 1909 — which he commissioned. That’s not reliable material for creating a factually accurate historical narrative.”

Gandhi has received recognition from a number of African leaders over the years. Friedrich thinks that’s irrelevant to the history. “Men like Haile Selassie, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Nelson Mandela have spoken well of Gandhi in the past, but they didn’t have access to the same information we have today. What would they say today if they could read modern scholarship instead of the sanitized materials they had access to decades ago?”

Referring to the 1906 Bambatha Uprising, when the colonial British government fought a war against Zulus, Friedrich adds, “In 1925, Gandhi told the world that he joined the British Army because he wanted to provide medical care for the Zulus, but he leaves out that he spent a year publishing newspaper articles calling on Indians to fund British troops, to join the Army because ‘the whites want us to’, trying to convince the British to provide Indians with arms and weapons training, and demanding formation of a permanent armed Indian corps. Just look at what he wrote right before he went to the battlefield.”

Friedrich points to a June 1906 article by Gandhi where he wrote, “There is hardly any family from which someone has not gone to fight the Kaffir rebels. Following their example, we should steel our hearts and take courage. Now is the time when the leading whites want us to take this step.” The term “Kaffir,” a racial slur which was banned in South Africa in 1976, appears frequently in Gandhi’s writings. “Gandhi’s use of the K-word makes it inescapably obvious that he meant it in a derogatory sense,” says Friedrich. He notes an 1899 statement by Gandhi where he said, “Indians are undoubtedly infinitely superior to the Kaffirs.”

He asks, “Was this South African Gandhi just young and immature? Gandhi espoused racism against blacks from his mid-20s on into his 40s. Did he change and evolve? Well, he stopped promoting racial segregation once he returned to India, but that’s because he was no longer surrounded by a majority black African population. He never admitted to making these remarks or taking these actions. He never retracted his statements. He never apologized for them. Do we consider a man to have evolved beyond racism if he doesn’t take responsibility for his actions and express remorse?”

“Compare Gandhi’s statements with Dr. King’s,” concludes Friedrich. He refers to King’s famous 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech, where he said, “I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists… one day, right there in Alabama, little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.” Yet, asks Friedrich, “What did Gandhi want? In 1905, he was demanding segregated schools.” He refers to a letter Gandhi wrote to the colonial government protesting that “the decision to open the school for all Coloured children is unjust to the Indian community” and demanding “that the school will be reserved for Indian children only.”

Meanwhile, an October 12, 2018 statement by the “Mahatma Gandhi Statue Must Fall Movement” in Malawi says, “We would like to demand that the project to erect the statue discontinues.” The statement also declares, “The statue is being forced upon the people of Malawi and is the work of a foreign power aiming at promoting its image and dominion on the unsuspecting people of Malawi.”

Responding to these claims, Arvin Valmuci of Organization for Minorities of India (OFMI) comments, “His statue has no place anywhere in the world, but Gandhi must fall most certainly in Africa. In South Africa, in Ghana, and now in Malawi, we stand in solidarity with all Africans who are rising up to protest against honoring a man who degraded them while living in Africa.”

Valmuci adds, “India’s imposition of a Gandhi statue in Malawi represents a neo-colonial attempt to control Africans, deny them equality, and continue to treat them as inferior. We remind India that the true hero of the Mulnivasi Bahujan — the original and majority population — is Dr. Bhim Rao Ambedkar, the great intellectual and champion of the Dalit Civil Rights Movement. Ambedkar and Gandhi were enemies.”

Speaking in 1955 about his interactions with Gandhi, Ambedkar stated, “I always say that, as I met Mr. Gandhi in the capacity of an opponent, I’ve a feeling that I know him better than most other people, because he opened his real fangs to me.”

Friedrich provides a brief timeline of Gandhi in South Africa —

Gandhi was 24 in 1893 when he arrived in South Africa with a law degree from London.

Gandhi was 26 in 1895 when he successfully created a three-tiered system of racial segregation by demanding a third door at the Durban Post Office.

Gandhi was 27 in 1896 when he wrote: “Ours is one continual struggle against a degradation sought to be inflicted upon us by the Europeans, who desire to degrade us to the level of the raw Kaffir whose occupation is hunting, and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with and, then, pass his life in indolence and nakedness.”

Gandhi was 30 in 1899 when he wrote: “Indians are undoubtedly infinitely superior to the Kaffirs.”

Gandhi was 34 in 1903 when he wrote: “Whereas Kaffirs are taxed because they do not work at all or sufficiently, we are to be taxed evidently because we work too much, the only thing in common between the two being the absence of the white skin.”

Gandhi was 34 in 1903 when he wrote: “We [Indians] believe as much in the purity of race as we think [the whites] do, only we believe that they would best serve the interest, which is as dear to us as it is to them, by advocating the purity of all the races and not one alone. We believe also that the white race of South Africa should be the predominating race.”

Gandhi was 36 in 1905 when he wrote that “the Kaffirs are of no use” and “the Kaffir hardly works.”

Gandhi was 36 in 1905 when he demanded Indians join the British Army to fight Zulu freedom fighters and wrote: “There is hardly any family from which someone has not gone to fight the Kaffir rebels, following their example, we should steel our hearts and take courage. Now is the time when the leading whites want us to take this step.”

Gandhi was 36 in 1906 when he called the British to “make use of, for purposes of war, one hundred thousand Indians” in the fight against the Zulus.

Gandhi was 36 in 1906 when he demanded an armed Indian corps, saying: “It is not for us to say whether the revolt of the Kaffirs is justified or not…. The common people in this country. keep themselves in readiness for war. We, too, should contribute our share.”

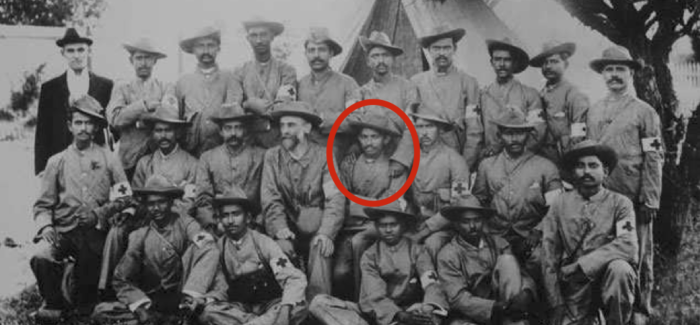

Gandhi was 36 in 1906 when he enlisted as a Sergeant-Major in the colonial British Army and joined the war against Zulu freedom fighters.

Gandhi was 37 in 1907 when he wrote: “Kaffirs are as a rule uncivilized…. They are troublesome, very dirty, and live almost like animals.”

South Africa officially established apartheid in 1948.

Following is a transcript of Friedrich’s lecture —

In 1925, ten years after Gandhi left South Africa, he first began writing and publishing his autobiography. Gandhi introduces his autobiography by stating, “[It] is not my purpose to attempt a real autobiography. I simply want to tell the story of my numerous experiments with truth… as my life consists of nothing but those experiments.”

A large portion of Gandhi’s autobiography consists of relating the events of his time spent in South Africa. Two claims particularly resonate with a modern audience.

First, Gandhi claims that he was the victim of racial prejudice in 1893. After buying a first class train ticket, he writes that he was thrown off the train for being a “colored” man riding in a first class compartment. In his autobiography, he says this made him ask, “Should I fight for my rights or go back to India?” According to Gandhi, he decides,

“It would be cowardice to run back to India without fulfilling my obligation. The hardship to which I was subjected was superficial – only a symptom of the deep disease of colour prejudice. I should try, if possible, to root out the disease and suffer hardships in the process.”

Second, Gandhi talks about how he joined the British Army in 1906 during a war to suppress an uprising of Zulus against the colonial British government. He claims that his motivation for enlisting with the Army which was fighting against the Zulus was to provide medical care for the Zulus. Gandhi writes,

“To hear every morning reports of the soldiers’ rifles exploding like crackers in innocent hamlets, and to live in the midst of them was a trial. But I swallowed the bitter draught, especially as the work of my Corps consisted only in nursing the wounded Zulus. I could see that, but for us, the Zulus would have been uncared for…. My heart was with the Zulus…. I was delighted… that our main work was to be the nursing of the wounded Zulus.”

So, a lot could be said about Gandhi’s life in South Africa. About how he started an ashram. About how he founded a newspaper called The Indian Opinion. About how he collaborated with Reverend Joseph Doke and commissioned this man to produce a biography of himself, of Gandhi. How Gandhi traveled to England to find a publisher for his own biography. How Gandhi expressed his desire of “buying out the whole of the edition.” Or how Gandhi worked to distribute complimentary copies of his biography to newspapers and famous people around the world.

Instead of talking about these things, let’s discuss Gandhi’s claims in his autobiography that,

1. He joined the British Army to help Zulus wounded by British soldiers.

2. His goal in South Africa was to root out the disease of color prejudice.

Conflict between the Zulus and the Colonial government began smoldering in 1905. In 1906, it ignited into full out war.

The Zulu War is actually more commonly known as the Bambatha Uprising, and it is considered the beginning of the African struggle against apartheid-style policies in South Africa.

The war began after Zulus killed two British tax collectors to protest a new head tax — a poll tax that was applied based on each individual person. Each individual in the community had to pay a tax for existing. So, from February to July 1906, the Zulu chief Bambatha led his people in an armed struggle against colonial oppression in South Africa.

In his 1925 autobiography, Gandhi claims that he learned of the war through the newspapers, writing,

“The papers brought the news of the outbreak of the Zulu ‘rebellion’…. I bore no grudge against the Zulus. They had harmed no Indian. I had doubts about the ‘rebellion’ itself.”

Do Gandhi’s writings during the Zulu War tell the same story as his writings from 20 years after the war, in his autobiography, when he first told the world about what he did during that war?

In 1905 articles in his newspaper, The Indian Opinion, Gandhi was already asking for Indians to be included in the British Army.

In November 1905, three months before the Zulu rebellion began, Gandhi writes, “If the Government only realised what reserve force is being wasted, they would make use of it and give Indians the opportunity of a thorough training for actual warfare.”

In December 1905, Gandhi praises a law allowing the Colonial government to raise “a force of Indian Immigrants Volunteer Infantry.” This law, he argues, permits Indians the opportunity to participate in “actual warfare.” Drawing on his expertise as an attorney, Gandhi writes, “If the Government only wanted the Indian immigrant to take his share in the defence of the Colony, which he has before now shown himself to be quite willing to do, there is legal machinery ready made for it.”

In March 1906, Gandhi publishes a plea for Indians to volunteer in the British Army, writing, “The Natal Native trouble is dragging on a slow existence…. The white colonists are trying to cope with it, and many citizen-soldiers have taken up arms.” Gandhi suggests that the conflict would end swiftly if the the Colonial government only made use of the military strength of the Indians. He writes, “There is a population of over one hundred thousand Indians in Natal [South Africa]. It has been proved that they can do very efficient work in time of war.”

In April 1906, Gandhi describes the conflict between the Zulus and the British. The Colonial government faced a tough fight is what Gandhi suggested. He writes,

“The region in which Bambatha is operating as an outlaw is in difficult terrain full of bushes and trees where the Kaffirs can remain in hiding for long periods. To find them out and force a fight is a difficult job.”

After painting this picture, Gandhi then asks, “What is our duty during these calamitous times in the Colony?” And he writes,

“It is… our duty to render whatever help we can…. If the Government so desires, we should raise an ambulance corps. We should also agree to become permanent volunteers…. The common people in this country keep themselves in readiness for war. We, too, should contribute our share.”

Again, in April 1906, Gandhi complains about “the criminal folly of not utilizing the admirable material the Indian community offers for additional defensive purposes [of the Colony].” The right move, he argues, was to train Indians to fight. Gandhi writes, “It is surely elementary wisdom to give [the Indian population] an adequate military training.”

Finally, in May 1906, Gandhi writes a final appeal for Indians to volunteer for the British Army. He complains, however, “The pity of it is that… the Government, have not taken the elementary precaution of giving the necessary discipline and instruction to the Indians. It is, therefore, a matter of physical impossibility to expect Indians to do any work with the rifle.”

While Gandhi considered it a pity that Indians had not been adequately trained to use rifles, he was convinced that the community could still serve as a great asset in times of war. He concludes, “It cannot be seriously argued that there is any wisdom or statesmanship in blindly refusing to make use of, for purposes of war, one hundred thousand Indians.”

In June 1906, the Colonial government finally accepted Gandhi’s demands to form an Indian corps. As Gandhi writes, “Acceptance by the Government synchronizes with the amendment of the Fire-Arms Act, providing for the supply of arms to Indians.” Although the Indian Corps was formed as a temporary body, Gandhi was still not entirely satisfied. He explains,

“Should [Indians] be assigned a permanent part in the Militia, there will remain no ground for the European complaint that Europeans alone have to bear the brunt of Colonial defence.”

Subsequently, Gandhi began encouraging Indians to subscribe to a Soldier’s Fund to support the British Empire’s troops in battle. Indians, he argued, should go to the front, but he insists that those who could not do so should “raise a fund for the purpose of sending the soldiers fruits, tobacco, warm clothing, and other things that they might need.” Why? Because, writes Gandhi, “It is our duty to subscribe to such a fund.”

So, the Indian Corps was assigned to work as Stretcher-Bearers. But Gandhi viewed it as an opportunity to get his foot in the door and to start working towards a bigger goal — creation of an armed Indian Corps. Writing in June 1906, he explains his strategy,

“The Stretcher-Bearer Corps is to last only a few days. Its work will be only to carry the wounded, and it will be disbanded when such work is no longer necessary. These men are not allowed to bear arms. The move for a Volunteer Corps is quite different and much more important. That Corps will be a permanent body; its members will be issued weapons, and they will receive military training every year.”

In the last newspaper article Gandhi writes before going to the battlefield, he issues a stirring call for other Indians to join him. “There is hardly any family from which someone has not gone to fight the Kaffir rebels,” declares Gandhi. “Following their example, we should steel our hearts and take courage. Now is the time when the leading whites want us to take this step.”

Gandhi then went to war in June 1906. He was appointed as a British Sergeant-Major. From the battlefield, Gandhi sent regular dispatches back to his newspaper, The Indian Opinion. From June 26 to July 19 — a three-week period — the Indian Corps was at war, serving with the British colonial forces in an armed struggle to suppress an uprising of black Africans against colonial oppression.

Of course, Gandhi’s autobiography says that his heart was with the Zulus and his work consisted of nursing wounded Zulus. Keep that in mind for the next few moments. From his battlefield dispatches, we discover the following —

On June 26, some Indians had to “dress the wounds on the backs of several Native rebels, who had received lashes.”

On June 27, the Corps had to “take a stretcher to carry one of the [British] troopers who was dazed” and also assist “in treating [a] wounded trooper, and others, who had received slight injuries.”

On June 28, the Corps had to take a British “Private… whose toe was crushed under a wagon wheel.”

On July 3, Gandhi says “we had a narrow escape” when “we met a Kaffir who did not wear the loyal badge. He was armed…. However, we safely rejoined the [British] troops.”

On July 10, after “narrowly escaping” from a Zulu who did not wear “the loyal badge,” Gandhi reports, “We finished the day… with no Kaffirs to fight.” The Corps did, however, help one wounded Zulu. Gandhi reports that, “A Kaffir, being a friendly boy” — who did wear “the loyal badge” — was mistakenly shot by a British trooper. The boy was “was badly wounded, and required carrying.”

On July 11, Gandhi reports that Indian Corps was assigned “about 20 Kaffir[s]… to help us.” Describing his experience working with these black African Zulus, Gandhi states, “The Natives in our hands proved to be most unreliable and obstinate. Without constant attention, they would as soon have dropped the wounded man as not.”

Shortly after, the war ended. The Indian Corps went home.

The outcome of this war was a British victory. A resounding British victory. An overwhelming British victory with 36 British killed. On the other side, the Zulu side, as many as 4,000 were killed, 4,000 were flogged, and 7,000 were imprisoned.

Gandhi, however, was very pleased with the role that he played in the British Army during this war. In August 1906, he reports, “Members of the Corps were all untrained and untried men; they were called upon, too, to do responsible and independent work, and to face danger unarmed.” Indians, Gandhi insists, had proved themselves capable of actual warfare. And so, writes Gandhi, “If the Government would form a permanent Ambulance Corps, I think that special training is absolutely necessary, and that they should all be armed for self-protection.”

Perhaps Gandhi’s decision to participate in the war against the Zulus can be understood in context of his opinion of the black Africans. In November 1906, three months after this war ended, Gandhi claims that there are “evident and sharp distinctions that undoubtedly exist between British Indians and the Kaffir races in South Africa.” Throughout previous years, he details his opinion.

In 1905, when the Colonial government allowed Africans to attend the same school as Indians, Gandhi writes the the government in protest. He says, “The decision to open the school for all Coloured children is unjust to the Indian community.” He asks “that the school will be reserved for Indian children only.”

Earlier that year, Gandhi claims that Indian labor is in high demand because “the Kaffirs are of no use” and “the Kaffir hardly works.”

In 1904, when the government was allowing Africans to share neighborhoods with Indians, Gandhi complains,

“The Town Council must withdraw the Kaffirs from the Location. About this mixing of the Kaffirs with the Indians, I must confess I feel most strongly. I think it is very unfair to the Indian population and it is an undue tax on even the proverbial patience of my countrymen.”

In 1903, Gandhi protests against a new tax — a head tax — which applied equally to both Africans and Indians. Gandhi suggests, “Whereas Kaffirs are taxed because they do not work at all or sufficiently, we are to be taxed evidently because we work too much, the only thing in common between the two being the absence of the white skin.”

Speaking of white-skinned people, in 1903, Gandhi also declares,

“We [Indians] believe as much in the purity of race as we think [the whites] do, only we believe that they would best serve the interest, which is as dear to us as it is to them, by advocating the purity of all the races and not one alone. We believe also that the white race of South Africa should be the predominating race.”

And, in 1899, Gandhi writes, “Indians… are undoubtedly infinitely superior to the Kaffirs.” So, finally, Gandhi presents his general opinion of black Africans in 1896. They were, he insisted, pitted against the Indian community. He writes,

“Ours is one continual struggle against a degradation sought to be inflicted upon us by the Europeans, who desire to degrade us to the level of the raw Kaffir whose occupation is hunting, and whose sole ambition is to collect a certain number of cattle to buy a wife with and, then, pass his life in indolence and nakedness.”

Such were Gandhi’s views, which were sometimes translated into actions, especially in the case of his participation in the Zulu War of 1906. His earliest actions, the success of which he later boasted about to audiences in India, similarly exposed the reality of his racial views.

In 1895, Gandhi began his public life by leading a campaign in the City of Durban. Speaking to an audience in Gujarat during a visit of India in 1896, he framed the issue as an example of the South African Indian community’s victories. Summarizing the problem, he states,

“I may further illustrate the proposition that the Indian is put on the same level with the native in many other ways also. Lavatories are marked ‘natives and Asiatics’ at the railway stations. In the Durban Post and telegraph offices there were separate entrances for Natives and Asiatics and Europeans. We felt the indignity too much…. We petitioned the authorities to do away with the invidious distinction.”

Describing the campaign in an 1895 report of his organization, the Natal Indian Congress, he writes, “Correspondence was carried on… with the Government in connection with the separate entrances for the Europeans and Natives and Asiatics at the Post Office.” The Government was moved by the correspondence and listened to Gandhi’s petition. “They have now provided three separate entrances for natives, Asiatics and Europeans,” he explains. Gandhi was pleased with the outcome writing, “The result has not been altogether unsatisfactory. Separate entrances will now be provided for the three communities.”

Thus, as a result of Gandhi’s legal efforts, colonial South Africa’s two-tiered system of racial segregation became a three-tiered system as blacks were separated from Indians. Indians no longer “had to share” a door with native South Africans. In other words, fulfilling Gandhi’s request, Indians and blacks were racially segregated. Again — fulfilling Gandhi’s request.