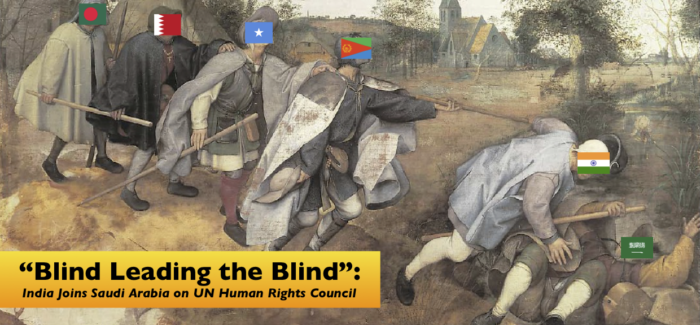

“Blind Leading the Blind”: India Joins Saudi Arabia on UN Human Rights Council

Admin | On 18, Oct 2018

Critics call it “a sham to task the most remorseless violators with protecting human rights”

GENEVA, Switzerland: Oct. 18, 2018 — The poet Rupi Kaur writes, “Do not look for healing at the feet of those who broke you,” a sentiment resonating with some ethnic and religious minority communities after India’s October 12 election to the United Nations Human Rights Council (HRC).

The HRC’s responsibilities include evaluating the records of member states on a variety of human rights issues, including freedoms of religion and speech, rights of racial and ethnic minorities, and women’s rights. Some groups, including Human Rights Watch (HRW), are criticizing the lack of competition in the process. All candidates, including India, were guaranteed election because there were only 18 candidates for 18 slots.

However, India as well as several other newly-elected members are also drawing criticism for allegedly violating many of the rights they are intended to protect — controversy which reflects the outrage when Saudi Arabia was elected to chair the HRC’s advisory committee in 2015. “The HRC exists to shape international human rights standards, but it’s a sham to task the most remorseless violators with protecting human rights,” states Arvin Valmuci, a spokesperson for Organization for Minorities of India (OFMI). “India joins the ranks of Saudi Arabia and several other nations who are all competing with each other to win the world record for most oppressive nation.”

Besides India, new members whose records are being questioned include Bahrain, Bangladesh, Cameroon, Eritrea, the Philippines, and Somalia. In a statement issued the day before the vote, HRW advised, “United Nations member countries should oppose the candidacies of the Philippines and Eritrea for the Human Rights Council because of their egregious human rights records.” Describing the process as a “mockery,” the group’s UN director, Louis Charbonneau, questioned the “credibility and effectiveness” of the HRC when they are “putting forward serious rights violators and presenting only as many candidates as seats available.”

“These other nations deserve extreme censure for their atrocious records on human rights, but India deserves special attention as it is not only by far the most populous of the seven suspect states but also routinely proclaims itself as the world’s largest democracy,” comments Pieter Friedrich. An analyst of South Asian affairs, he asks, “Why is India even a member of the United Nations when it not only regularly violates key elements of the UN Declaration of Human Rights but is also one of the only countries in the world which consistently refuses to participate in foundational international treaties?”

India was a founding member of the UN in 1945, and signed the Geneva Convention, but it has not signed the two additional protocols passed in 1977. Out of 193 member nations, 174 have passed (signed and ratified) Protocol I while 168 have passed Protocol II. Additionally, since 1951, India has passed only six of nine core international human rights instruments. It has signed but not ratified the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (1984) and the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (2006). It refuses to sign the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (1990). Furthermore, India has passed only two of nine optional protocols which augment the nine instruments.

Other major international treaties in which India refuses to participate include the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1951), the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (1968), the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (1996), and the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (1998). All of these treaties have been signed by at least 75 percent of other member nations.

The Rome Statute, which established the International Criminal Court, enables the court to investigate and punish perpetrators of four core crimes: genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression. Signatories agree to extradition of suspects. However, India has not only refused to participate but, in December 2002 (nine months after allegedly state-sponsored mass violence in Gujarat), signed a bilateral non-extradition treaty with the United States.

“When considering the level of freedom in a society, which is really what human rights is all about, the most important factors are freedom of religion or belief, freedom of the press, and the status of women,” remarks Friedrich. “All three factors are central to a peaceful and dignified human existence. India currently ranks as the most dangerous country in the world for women, in the top 50 worst countries for press freedom, and neck-and-neck with Saudi Arabia when it comes to religious freedom.”

Freedom of Religion

According to Pew Research Center’s 2018 report on restrictions on religion, India is among the 25 most populous countries with the highest levels of religious restriction. Pew ranks the level of government restrictions in India as “high” (a category which Bahrain, Bangladesh, and Somalia also share while Eritrea is categorized as “very high”) but ranks it as having the world’s highest levels of social hostilities against other religions as perpetrated by groups or individuals.

The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom’s 2018 report ranks India as one of 12 Tier 2 countries which the commission believes “require close monitoring due to the nature and extent of violations of religious freedom engaged in or tolerated by governments.” Bahrain, Eritrea, and Saudi Arabia are categorized as three of 16 Tier 1 “countries of particular concern,” while Bangladesh and Somalia are listed as two of nine monitored countries.

The 2018 “World Watch List” compiled by Open Doors, a group which deals with international persecution of Christians, ranks India as the 11th most dangerous country in the world to be a Christian. Somalia ranks 3rd, Eritrea ranks 6th, and Saudi Arabia ranks 12th.

Saudi Arabia officially protects the right to freely practice religion only in private, while Article 25 of India’s Constitution protects the right to publicly practice as well as propagate religion. Article 25, however, makes freedom of religion conditional on vague requirements that it must be “subject to public order.” The article has not prevented enactment of “anti-conversion” laws which regulate religious conversion. Nine Indian states have adopted such laws, which typically require notification or even permission of local authorities before a person is allowed to change their religion. The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has repeatedly expressed its intention to draft a similar national law.

Heiner Bielefeldt, who was the UN’s Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief from 2010 to 2016, called such laws “disrespect of freedom of religion or belief.” He said that converts “have to undergo, I’d say, a humiliating bureaucratic procedure, exposing themselves and explaining the reasons [for their conversion] as if the State were in a position of being able to assess the genuineness of conversion.” He also warned that the laws are “applied in a discriminatory manner” and biased in favor of Hinduism. He suggested they also encourage social hostilities — which, according to Pew, are highest in India — stating, “Acts of violence are part of a broader pattern of instigating fear into the minorities, sending them a message they don’t belong to this country unless they either keep at the margins or turn to Hinduism.”

Additionally, India has recently tolerated a wave of mob lynchings of citizens, primarily Muslims and Dalits, who are accused of possessing beef or slaughtering cattle. Laws in 13 of India’s 29 states completely ban the slaughter of all cattle, while cattle slaughter is criminalized to one degree or another in a total of 21 states. These laws encourage social hostilities by upper-caste Hindus (who worship cows) against Dalits and all non-Hindus (who frequently eat beef).

Violence related to cow protection has been a feature of Indian society for a long time, but the country has undergone a massive spike in incidents since 2014. Journalism website IndiaSpend, which conducted the first statistical analysis of cattle-related attacks and lynchings, documented and analyzed all reported incidents from 2010 to mid-2017. “Of 63 attacks recorded since 2010, 61 took place under Mr. Modi’s government,” reported IndiaSpend in June 2017.

Further data analysis reveals several shocking trends. Of 28 people killed, 24 were Muslim. Out of 63 attacks, 32 victims were Muslim, five were Dalit, and one was Christian. In 13 of 63 attacks, police pressed charges against the victims. In 23 of 63 attacks, the attackers were identified as members of Hindu nationalist groups. Of 63 attacks, 32 occurred in states governed by the BJP. Finally, 2017 saw a 75% increase in attacks versus the same period in 2016.

Freedom of the Press

According to Reporters Without Borders’s (RWB) 2018 ranking of press freedom in 180 countries, six of the seven new HRC members with questionable human rights records are among the 50 worst countries in the world. Out of 180, Eritrea is 179th, Somalia is 168th, Bahrain is 166th, Bangladesh is 146th, India is 138th, and the Philippines is 133rd. Saudi Arabia ranks at 169th. Aside from abuses and violence against journalists, the rankings are determined based on “pluralism, media independence, media environment and self-censorship, legislative framework, transparency, and the quality of the infrastructure that supports the production of news and information.”

Freedom of the press is stringently censored in Saudi Arabia. As RWB reports, “Saudi Arabia permits no independent media and tolerates no independent political parties, unions, or human rights groups. The level of self-censorship is extremely high and the Internet is the only space where freely-reported information and views may be able to circulate, albeit at great risk to the citizen-journalists who post online.”

In contrast, however, India fares little better. India has no law protecting freedom of the press. Although Article 19 of India’s Constitution technically protects “freedom of speech and expression,” this provision — like Article 25 — also contains broad and vague conditions which empower the government to curtail the press for reasons ranging from “integrity of India” to “friendly relations with foreign States,” “public order,” and “preserving morality.” In practice, RWB explains, “journalists who are overly critical of the government” are prosecuted while others are charged with sedition for writing about India’s territorial structure. RWB reports, “With Hindu nationalists trying to purge all manifestations of ‘anti-national’ thought from the national debate, self-censorship is growing in the mainstream media and journalists are increasingly the targets of online smear campaigns by the most radical nationalists, who vilify them and even threaten physical reprisals.”

In October 2018, Saudi Arabian government officials reportedly murdered Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi while he was in the Saudi embassy in Turkey. He had been publishing articles which were increasingly critical of the Saudi regime. In September 2017, in contrast, Indian journalist Gauri Lankesh was assassinated by extremists. Her accused killers are affiliated with Sanatan Sanstha, a wing of Hindu Janajagruti Samiti, which is itself an offshoot of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). The RSS, to which a large portion of the BJP government’s cabinet ministers belong, allegedly operates as a deep state which actually operates the levers of power.

Describing circumstances as of 2017, HRW reports that targets of vigilante violence included “critics of the government” and attacks were often carried out by “groups claiming to support the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party.” In summary, HRW states, “Dissent was labeled anti-national, and activists, journalists, and academics were targeted for their views, chilling free expression.”

Status of Women

According to the Thomson Reuters Foundation’s 2018 report, India ranks as the most dangerous country in the world for women. Somalia ranks 4th. Saudi Arabia ranks 5th.

Citing India’s “rape epidemic,” the Foundation stated that India earned its rank based on “the risk of sexual violence and harassment against women, the danger women face from cultural, tribal, and traditional practices” and for being “the country where women are most in danger of human trafficking including forced labour, sex slavery, and domestic servitude.”

In 2018, two high-profile rapes garnered international attention after elected officials rallied in support of the accused rapists. In Kathua, Jammu and Kashmir, an 8-year-old Muslim girl was gang-raped in a Hindu temple before being murdered. Two BJP state ministers attended rallies on behalf of the accused. In Unnao, Uttar Pradesh, a BJP state legislator allegedly raped a 17-year-old girl and oversaw the murder of her father. Not only does he currently retain office, but the state party organized rallies on his behalf.

Other Human Rights Issues

India has been criticized for its record on a host of other human rights issues.

One of the leading issues is the practice of torture. The HRC conducts a Universal Periodic Review (UPR) which catalogues reports and comprehensively examines the performance of all UN member nations on human rights. For the 2012 UPR, OFMI submitted a report entitled, “Torture common by police officers in India.”

According to OFMI’s report, “The use of torture is employed as daily tool by Indian police officers.” The report further stated, “Torture is so universally accepted and encouraged among the ranks of India‟s police forces that it is a virtual certainty that anyone who is a police officer in India knows that torture occurs, has definitely been exposed to it, probably has participated in it, and almost certainly has helped cover it up.”

The report explained that torture is not a criminal act under Indian law. Internationally, India has not ratified the UN’s Convention Against Torture. Nationally, there is no legal definition of torture or prohibition of its practice. Furthermore, Indian law protects police who practice torture. Section 197 of the Criminal Procedure Code grants immunity to any government official alleged to have committed a criminal offense “while acting or purporting to act within the discharge of his official duty.” The report concluded, “Although the Indian government has not recently been implicated in the sorts of large-scale, ethnically targeted massacres of detainees by custodial torture as it was in the 1990s, the country’s political environment remains highly tolerant of and receptive to the use of torture.”

Other issues include mass enforced disappearances of civilians, which are typically believed or even proved to have ended in fake encounters or extrajudicial executions. Tens of thousands are victims of disappearances. In 1996, in Kashmir, human rights attorney Jalil Andrabi reported that over 40,000 — including “old men and children, women, sick and infirm” — had been killed since 1989. He was subsequently abducted by the Indian Army and killed in custody. In 1995, in Punjab, human rights activist Jaswant Singh Khalsa uncovered evidence that at least 25,000 Sikh youth had been victims of mass cremation since 1985. He was subsequently abducted by Indian Police and killed in custody. “Whether its mass graves in Kashmir, mass cremations in Punjab, razing villages in Chhattisgarh, or rampant torture, India has refused to confront and redress atrocities perpetrated by its security forces,” concluded American human rights attorney Sukhman Dhami in 2015. “In many cases, these crimes have been well documented by India’s own institutions and credible human rights organizations.”

Besides these issues, human rights groups continue to demand justice for pogroms — sometimes termed as genocides — against India’s religious minorities. Chief among these are the 1984 Sikh Genocide in Delhi and other regions, the 1992/93 pogroms against Muslims after the Babri Masjid destruction, the 2002 genocide of Muslims in Gujarat, and the 2008/9 pogroms against Christians in Odisha. Very few have been convicted for any of the incidents of violence, those who have been convicted are often already on bail, and charges have never been filed against top elected officials — including state legislators, chief ministers, and members of Parliament — who are implicated by victims, eyewitnesses, and even participants in the violence.

Friedrich says these issues are “only the tip of the iceberg.” He explains, “It’s difficult to briefly summarize the full extent of human rights abuses in India. We can talk about violations of basic rights, or the use of torture and perpetration of pogroms, but what about equally systemic issues which are invizibilized by their assumed normality? If we talk about acts of mass violence against minorities, for instance, we need to also discuss the deaths of manual scavengers, whose rights are violated on a day to day basis as a consequence of social acceptance of caste.”

Manual scavenging is the traditional practice of removal of human excrement by hand. India’s 2011 census documented 794,000 cases of manual scavenging across the country. According to filmmaker Divya Bharathi: “Neither the central government nor the state government is interested in rehabilitating manual scavengers…. All sanitary workers are manual scavengers.” Various laws at state and national levels have addressed the ongoing practice. Most notably, the Indian Parliament passed “The Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and Their Rehabilitation Act, 2013.” However, implementation of the laws is severely lacking.

Bezwada Wilson, an expert on the issue, has convened Safai Karmachari Andolan (Manual Scavengers Protest). In September 2018, he said that “states lack the political will to address manual scavenging.” Reporting that at least 300 manual scavengers have died at work since 2017, Wilson described the deaths as “murders by the state.” He says his evidence indicates there are 2.5 million manual scavengers nationwide, of which 160,000 are women.

“The political will to eradicate manual scavenging may be linked to acceptance of it as a legitimate caste-based practice,” comments Friedrich. “Manual scavengers are Dalits — formerly known as Untouchables or outcastes — and the caste system legitimizes their lot in life by calling it fate. They are considered humans of a lower value. Without viewing them as equally human, there’s no social incentivize to modernize sewage infrastructure or, at the very least, ensure these sanitation workers aren’t mucking out sewers with bare hands and naked bodies.”

Summarizing its findings in its 2017 report on human rights in India, the U.S. State Department cited a large number of the above documented issues, reporting:

“The most significant human rights issues included police and security force abuses, such as extrajudicial killings, disappearances, torture, arbitrary arrest and detention, rape, harsh and life-threatening prison conditions, and lengthy pretrial detention. Widespread corruption; reports of political prisoners in certain states; and instances of censorship and harassment of media outlets, including some critical of the government continued. There were government restrictions on foreign funding of some nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), including on those with views the government stated were not in the ‘national interest,’ thereby curtailing the work of these NGOs. Legal restrictions on religious conversion in eight states; lack of criminal investigations or accountability for cases related to rape, domestic violence, dowry-related deaths, honor killings, sexual harassment; and discrimination against women and girls remained serious problems. Violence and discrimination based on religious affiliation, sexual orientation, and caste or tribe, including indigenous persons, also persisted due to a lack of accountability.”

Conclusion

Reacting to India’s election to the HRC, UK-based OFMI spokesperson Charity Joseph calls it “the blind leading the blind.” She comments, “Entrusting an oppressive nation with combatting oppression is not only the height of hypocrisy, but as a Christian of Indian origin it reminds me of the words of Jesus.” She quotes from the book of Matthew, where Jesus stated, “Let them alone; they are blind guides. And if the blind lead the blind, both will fall into a pit.”

While India draws criticism for its domestic human rights record, its foreign policy focuses on an expanding footprint in Africa. Its approach involves grants, loans, and investments in infrastructure, but it is not without controversy. In Malawi, for instance, protests are erupting after India required installation of a statue of Mohandas Gandhi as a condition for building a $10 million dollar convention centre. A coalition formed to oppose the statue, citing Gandhi’s racism against black Africans during his 21 years as a lawyer in South Africa, stated, “The statue is being forced upon the people of Malawi and is the work of a foreign power aiming at promoting its image and dominion on the unsuspecting people of Malawi.”

“We are horrified by the arrogance of the Statues for Development agenda forced on Africans,” comments Valmuci. He adds, “This is a new tactic of Brahmanism, the caste supremacist ideology which has afflicted India for thousands of years. They seek to purchase the dignity of people in exchange for trinkets and toys. Gandhi, who preached Brahmanism, praised Aryans as the highest race, and espoused racism against blacks before later sexually exploiting his grandnieces, is a sad example of the terrible condition of human rights in modern India. The government of India wants to present a glamorous image of peace and nonviolence, but it loses all moral high ground as it continues to export as its representative a racist sexual predator whose legacy is rejected by the Mulnivasi Bahujan population of the Indian subcontinent.”

“We look to the words of the Guru Granth Sahib for guidance,” concludes Valmuci. “We know that healing will never be found at the feet of those who broke us. Instead, we have faith in a higher justice.” Valmuci quotes a passage composed by Guru Nanak, who wrote:

“The kings are tigers, and their officials are dogs; They go out and awaken the sleeping people to harass them. The public servants inflict wounds with their nails. The dogs lick up the blood that is spilled. But there, in the Court of the Lord, all beings will be judged. Those who have violated the people’s trust will be disgraced; their noses will be cut off.”