Irom Sharmila, World’s Longest Hunger-Striker, Weds in Tamil Nadu

Divya Bharathi, persecuted for anti-caste documentary, serves as bridesmaid

Kodaikanal, Tamil Nadu: August 17, 2017 — After a lengthy engagement during which her fiancé often questioned the possibility it would end in nuptials, Manipuri hunger-striker Irom Sharmila has finally wed Desmond Coutinho in Tamil Nadu.

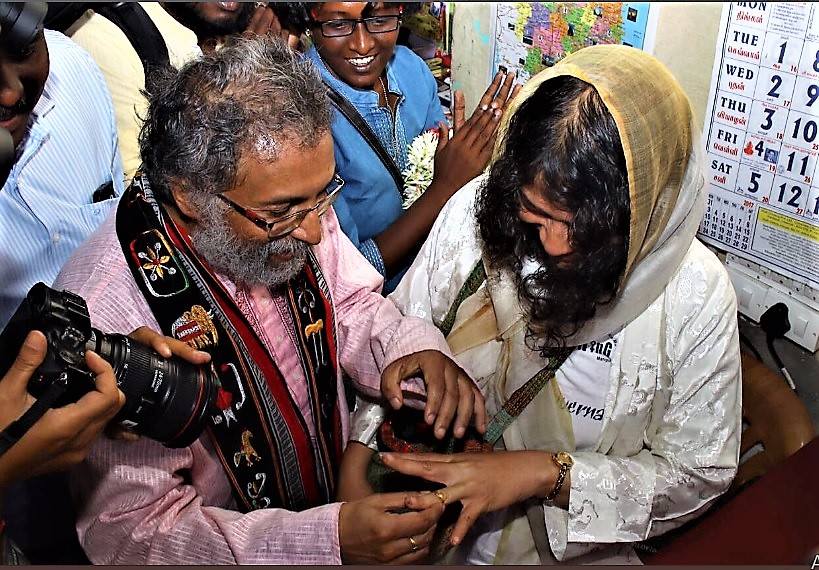

In a simple ceremony on August 17, Sharmila and Coutinho formalized their marriage at the government registrar office in the mountainous town of Kodaikanal. They were joined by three witnesses, as well as Madurai filmmaker Divya Bharathi, who held a bouquet of roses as she served as Sharmila’s bridesmaid. Bharathi has recently faced death threats and criminal charges for her documentary exposing caste-based manual scavenging in Tamil Nadu, but she’s gained the outspoken support of Sharmila.

Sharmila gained international attention and admiration for her 16-year hunger-strike against India’s Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), which grants impunity to Indian security forces for any actions committed on duty. After beginning her fast on November 5, 2000, she was immediately charged with attempted suicide, imprisoned in a hospital, and fed by authorities via a nasal tube. Nicknamed the “Iron Lady of Manipur” for her resolve, she finally ended her fast in August 9, 2016.

In 2015, Sharmila pledged, “After I am getting married to my fiancé, Desmond, I will never stop [being] committed to social works.” Before her wedding ceremony in Kodaikanal, she again commented about her plans for activism. “I want to stop, but I can’t,” says Sharmila.

Among the activism which the former hunger-striker intends to pursue is a continued demand for repeal of AFSPA. “I dedicated over 16 years to the removal of the AFSPA,” she wrote in a statement released the day before her wedding. “I promise to the dead and to the survivors of this Draconian Law to pursue its repeal by non-violent means…. I will continue to do all I can to bring this draconian colonial law to the attention of those in power using nonviolent, loving persuasion. The democratically elected government of an independent nation must not rule as our former imperial masters.”

Sharmila’s bridesmaid, Bharathi, earned the bride’s admiration after enduring a wave of persecution for her documentary, “Kakkoos.” The film reveals the daily lives of “manual scavengers,” sanitation workers who are forced to clean human excrement using their bare hands. It exposes how the Tamil Nadu government refuses to properly implement “The Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and Their Rehabilitation Act, 2013.” Many of her interview subjects work as government employees in municipal sanitation departments; the departments have safety equipment, say workers, but their supervisors refuse to issue it.

Bharathi linked the ongoing existence of manual scavenging to the practice of caste. Bezwada Wilson, an activist interviewed in her film, explains, “Only if we get rid of the caste from our minds can we think of providing other jobs to these people.” As explained by the movement which Wilson cofounded to eradicate manual scavenging further, “The caste system dictates that those born into a particular Dalit sub-caste should engage in manual scavenging and should remain doing so throughout their lives, prohibiting them to lead a dignified life in the community.”

In response to her film, says Bharathi, “I received around 2000 calls abusing and threatening to rape and kill me.” Furthermore, she was slapped with criminal charges by police, who accused her of cyber terrorism for releasing “Kakkoos” online and of promoting enmity between groups because the documentary names specific castes.

Sharmila, however, responded with solidarity. “I will stand by Divya; I hope you will do the same. I invite Divya to stand beside me at my wedding next week. At this moment, I cannot think of a finer garland than the end of caste slavery,” Sharmila told reporters in Madurai on August 10. In her August 16 statement, she again affirmed Bharathi, writing:

“I am hoping to stand tomorrow with Divya Bharathi, a documentary filmmaker who exposed the caste slavery system in her film, ‘Kakkoos.’ She sought only the implementation of the Manual Scavengers Act 2013 and to speak for those who have no helpers. It is so sad that freedom of speech and association is now outlawed in India…. We must not compel our brothers and sisters to do work that we would never undertake ourselves.”

In a post to her Facebook, Bharathi said she was feeling blessed, writing (in Tamil), “Today’s day is only my whole life.” The filmmaker was also offered some relief from her legal troubles. The day before the Sharmila/Coutinho wedding, the Madurai bench of the Madras High Court temporarily suspended criminal charges against her, arguing that “Kakkoos” contains no objectionable content.

Sharmila’s romance with her husband has been a long and dramatic affair. Coutinho first met Sharmila in Imphal, Manipur in 2011 after exchanging letters for two years. “No one told me you’re not supposed to flirt with a hunger-striker,” he explained in 2016. “She wrote back, asking if she had misunderstood and if I would clarify my intentions.”

A second-generation African with British citizenship, Coutinho repeatedly traveled to and from Imphal to visit Sharmila. They quickly became engaged. In 2014, however, he was arrested after protesting when police denied him access to his fiancée. He was imprisoned for 77 days before charges were finally dropped, after which he was booted from the country.

In 2015, while still on hunger-strike, Sharmila expressed her desire to unite with Coutinho. “I want to commit to him, my life partner, just like a couple of peace birds to give message of hope to the world,” she said. Meanwhile, Coutinho never gave up hope, although he sometimes questioned whether their love would ever be fulfilled. In Spring 2016, he remarked, “The only thing I want for her is to try and stay alive this year. I can’t see a way forward.”

After Sharmila ended her hunger-strike, Coutinho traveled from his home in Ireland to be with her. He arrived in India in Spring 2017, and the couple settled in Tamil Nadu. Their move was met with opposition in some corners.

On August 4, the Hindu Makkal Katchi — a branch of the Hindu nationalist organization Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh — filed a legal petition to block the marriage. The group’s state secretary, R. Ravikumar, alleged, “If she really wanted to fight against human rights violations, she should go to Kashmir. Her stay would certainly attract international and local agitators to Kodaikanal and it would affect the peace.” Their petition was rejected.

The group recently headlines for a different reason. On July 19, two Christian pastors in the city of Nagapattinam were assaulted by a gang wielding steel rods and knives. The victims identified their attackers as members of the Hindu Makkal Katchi. One of the pastors, Daniel Jebraj, describes the incident as “Hindu extremist violence on Christians.”

Sharmila and Coutinho, however, are now married, after having overcome years of obstacles. “There has been some interest in social media around purported complaints or attempts to stop my marriage,” writes Sharmila in her August 16 statement. “I do not understand why my marriage is a matter for discussion by any groups who do not know us and who are not related to us. I have never heard of any other person’s marriage being talked about in this way. It remains puzzling.”

While Sharmila is the world’s longest hunger-striker, the world’s oldest hunger-striker also currently resides in India. Bapu Surat Singh Khalsa, 84, began a hunger-strike on January 16, 2015 to demand the release of Sikh political prisoners who have completed their sentences but remain behind bars. He has been repeatedly arrested and force-fed by authorities in Ludhiana, Punjab and he remains confined in police custody in Ludhiana Civil Hospital.

Speaking in June 2015, Sharmila expressed solidarity with Khalsa, saying, “Thank you for informing me about Bapu Surat’s hunger-strike.”

“I will continue to dedicate my life to service for as long as I can be of service,” stated Sharmila on August 16. “I hope that India becomes what it truly is and that others are inspired to a life of service before and for others rather than made fearful of it.”

“We wish a happy, peaceful, and quiet life to Desmond and Irom,” says Pieter Friedrich, an advisory director to Organization for Minorities of India. “I extend my deepest congratulations on their marriage. The years of patience, courage, and resolve demonstrated by both of them are a shining example for all of humanity.”