Editorial: First Asian in U.S. Congress Was a Sikh Inspired by Civil Rights Principles

Dalip Singh Saund spoke against “coddling kings and dictators and protecting the status quo”

The same year the United States passed the Civil Rights Act of 1957, an immigrant in California achieved the triple honor of becoming the first Asian, Indian, or Sikh to serve in the United States Congress — and so vote for the act to protect the rights of all U.S. citizens to vote.

Dalip Singh Saund emigrated from Punjab, India to study at the University of California, Berkeley in 1920, a time when Asians were denied the right to become citizens or even own land. Within forty years, he cracked the racial barrier for Asians to become federal elected officials. Upon arriving in Congress, he refused to play it safe, instead speaking out boldly for equal recognition of civil rights; as a member of the powerful Foreign Affairs Committee, he also raised his voice against using American taxpayer dollars to fund foreign aid bailouts.

Speaking on the floor of the House of Representatives on June 14, 1957, just four days before voting for the Civil Rights Act, Saund said: “No amount of sophistry or legal argument can deny the fact that in 13 counties in one State in the United States of America in the year 1957, not one Negro is a registered voter. Let us remove those difficulties.” Addressing supporters of segregation, he remarked, “Please modify your way of thinking. Look at the clock. Go ahead, and do not hold the game up.” [1]

Saund knew discrimination first-hand. He arrived in the United States at a time when the federal Chinese Exclusion Act treated all Asians as “Chinese” and banned them from citizenship. If he had arrived just a few years later, he would not have even been allowed in the country at all, as the 1924 Alien Exclusion Act firmly entrenched anti-immigrant laws by prohibiting anyone ineligible for U.S. citizenship from immigrating. In California, he also faced state laws like the 1913 Alien Land Law, which prohibited immigrants ineligible for citizenship from owning land.

Although Saund faced a monumental struggle, he credited his parents for investing in his future: “My father and mother could not read or write. But when my parents made money, it was their first ambition to give their children the benefits of higher education.” Because his parents scraped by to send him to school, he learned to read. In 1917, while living in Amritsar, Punjab, he read speeches by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson printed in Indian newspapers. Saund said: “I was simply fascinated by the beautiful slogans of Woodrow Wilson – to make the world ‘safe for democracy,’ ‘war to end wars,’ ‘self-determination for all peoples.’” [2]

After earning a degree in mathematics from the University of Punjab in 1919, Saund left British-occupied India to pursue a future in the country whose president spoke of “self-determination for all peoples.” On arrival in California, he began studying agriculture at the prestigious UC Berkeley with patronage from Stockton Gurdwara, living in the gurdwara-owned Guru Nanak Khalsa Hostel. [3] Within two years, he was elected national president of the Hindustani Association of America and began speaking publicly for India’s independence from the British Empire.

“All of us,” he wrote about the association, “were ardent nationalists and we never passed up an opportunity to expound on India’s rights.” One one occasion, when he introduced a political science professor at an association event, Saund said, “First, I delivered a half-hour talk on the right of India to independence and the inequities of English rule.” [4]

The Stockton Gurdwara’s unflinching support for self-determination doubtless guided the future statesman’s ambitions. Recognized by the State of California on the anniversary of its 2012 centennial celebration as “the first permanent Sikh American settlement and gurdwara in the United States,” the gurdwara also formed the Ghadar Party in 1913. As declared by the California legislature, “The Ghadar Party was the first organized and sustained campaign of resistance to the British Empire’s occupation of the Indian subcontinent.” [5]

From its base in California, the Ghadar Party sent 616 members to spark an independence movement in India, of whom 527 were Sikhs. [6] Among those Sikhs was Kartar Singh Sarabha, who, like Saund, was a student at UC Berkeley. With funding from Stockton Gurdwara, a 17-year-old Sarabha founded The Ghadar in November 13, 1913 — the first Punjabi-language publication in the country, the newspaper remained in print until 1948 and is considered instrumental in achieving India’s independence. [7]

Sarabha returned to India in 1914 to join the struggle against the British. He was arrested not long after and hanged to death in Lahore, Punjab by British authorities on November 16, 1915. Saund, a 16-year-old living just 30 miles away in Amritsar, almost certainly heard about the martyred young freedom fighter Sarabha. Just two years later, Saund was inspired by Wilson’s speeches; soon, he arrived in the U.S. to study at the same university as Sarabha, also with patronage from Stockton Gurdwara as he joined his voice to the same call for independence.

In recent years, Saund’s nephew reported that his uncle was actually already involved with the Ghadar Party before he left India, and traveled to the U.S. partly because “the heat from the colonial authorities regarding his Ghadar activities was getting too much.” [8]

After beginning studies in agriculture at UC Berkeley, Saund switched to mathematics, earning a masters in 1922 and a doctorate in 1924. Despite his years of higher education, Saund said, “Because I could not become citizen of the United States, I could not find a teaching job.” So he moved several hundred miles south to take work as foreman of a cotton-picking crew. [9]

Recognizing his vigor for India’s freedom movement, Stockton Gurdwara maintained a relationship with the young Saund. Then, in 1930, the gurdwara commissioned him to write a manifesto of independence. Called “My Mother India,” the book offered a history of India and a plea for an end to its imperial occupation by the British. Saund said his book was intended to “answer various questions that commonly arise in the minds of the American people regarding the cultural and political problems of India.” [10]

The issue of India’s caste system was one of those common questions, and Saund’s book pleaded for the civil rights of the downtrodden in India as he compared caste in India to racism in America and elsewhere.

“Even in our present stage of advancement we find that caste prevails throughout the civilized world,” he wrote. “Its ugly symptoms are most prominent in America, Australia, and the white colonies of Africa. In the United States, the lynching of negroes in the South and the strict anti-Asiatic regulations of the state of California, and in Australia the ‘Keep Australia white at all cost’ spirit among the population — both of these show how deeply the spirit of race hatred has penetrated into the system of the dominant white races of the world.” [11]

Suggesting the Asian Exclusion Act legally enshrined “the caste of race,” Saund explained:

“In the state of California, which is the center of oriental population in America, law prohibits the Asiatics (Japanese, Chinese, Hindus) from owning property and even from temporarily leasing lands for farming purposes.… The anti-Asiatic land lease regulations of California have given a severe blow to the oriental population of the state…. The simple, peace loving, industrious, and retiring Asiatics who toiled to make the name of agricultural California great are barred by law from making even an honest, meager living through farming on a small scale. And all because of the caste of race.” [12]

His response to both Western and Eastern forms of racism was a call for “the purity of the human soul.” Excoriating caste practitioners and affirming racial equality, he wrote: “Let those who wish clamor loud about their Nordic superiority or Brahmanic purity. What is needed in the world today is not the purity of the race so much as the purity of the human soul and its motives…. By denying to their fellow brethren their rightful position as human beings, the upper classes of India have sinned most atrociously against themselves and their gods.” [13]

Saund concluded starkly: “India needs a reorganization of its antiquated social system in order to fit properly into the modern world.” [14]

After writing his book, Saund continued campaigning for a clear path to American citizenship for Asian Americans. In 1946, Congress passed the Luce-Cellar Act, finally opening the door for at least a handful of Asians to immigrate and allowing those already in the country to naturalize as citizens and own land. Saund immediately took advantage of this new freedom.

By 1949, Saund was a naturalized U.S. citizen. Since 1948, he had served as General Secretary of the Stockton Gurdwara, a position he held until 1950. That year, though, Saund discovered duty called him elsewhere — to serve as an elected official, a privilege now open to him by citizenship. He ran for county judge in southern California, losing his first election on a technicality but winning when he ran again in 1952.

As an Asian running for public office in a racially tense society, Saund faced discrimination even from voters he was running to represent. During his 1952 campaign, he said “a prominent citizen“ saw him in a restaurant and shouted: “Doc, tell us, if you’re elected, will you furnish the turbans or will we have to buy them ourselves in order to come to your court?”

Saund replied: “My friend, you know me for a tolerant man. I don’t care what a man has on top of his head. All I’m interested in is what he’s got inside it.” [15]

Having won his first election, the newly-minted judge wasn’t about to stop breaking racial barriers. In 1956, he ran to represent the 29th Congressional District of California. On January 1, 1957, he resigned his judgeship to take office as the first Asian, first Indian, and first Sikh elected to serve in the United States Congress.

For Saund, who had spent so many years speaking for freedom, his first priority as a United States Congressman was to demand equal civil rights for all U.S. citizens.

In 1947, India became independent — by 1957, the West African region of Ghana also gained independence from the British Empire. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., after spending the first months of the year establishing the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to organize civil disobedience campaigns against segregation, traveled to Ghana to join the independence festivities. While there, he drew parallels between the struggles against colonialism and against racism, saying: “Eventually the forces of justice triumph in the universe, and somehow the universe itself is on the side of freedom and justice.” That a colonized country should gain independence from the empire, King said, “Gives new hope to me in the struggle for freedom.” [16]

Meanwhile, Saund was in Washington, D.C. working to protect the votes of African-Americans by speaking on behalf of the Civil Rights Act.

In a speech given the week before the Act was passed, Saund said, “In the United States of America today we have built a splendid and glorious edifice of human rights and moral values.” Referring to another foreign-born member of the House, Saund asked rhetorically, “If he had been born in the State of Mississippi and born with a black skin, would he be a Member of the United States Congress today?” [17]

Saund, however, found his own personal history offered comforting evidence of the possibility for positive social change, stating: “Ten years ago, I was not only a foreigner, but I was an alien, ineligible to citizenship in the United States of America. Because of the opportunities that were open to me and that are open to everybody in this country, I, with the help of great Americans, acquired the right of citizenship. I received my citizenship papers, and today I have the honor to sit in the most powerful body of men on the face of this earth.” [18]

As the first Asian in U.S. Congress, Saund was swiftly added to the influential Foreign Affairs Committee. Soon after first taking office, he took a tour of several Asian countries including Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Indonesia, Singapore, the Philippines, Thailand, Burma, India, and, lastly, Pakistan. Reporting on his travels, he concluded that some of the biggest recipients of U.S. foreign aid, such as Taiwan and Vietnam, demonstrated “a feeling of actual hostility and definitely not of any warmth and friendship toward the people of the United States.” This surprised him. [19]

“Because those people were receiving such tremendous amounts of American aid from us, I expected, as an American, to be greeted with warmth and affection,” wrote Saund. “But the love of a people can never be bought by military aid.” The problem, he suggested, was that U.S. dollars were being handed out indiscriminately, so he warned: “You do not win hearts and minds by propping up dictators with gobs of military aid.” [20]

Shortly after returning from his tour of Asia, Saund was reelected to Congress in 1958 and again in 1960. Between his international travels, concern for civil rights, and years of experience gained serving on the Foreign Affairs Committee, Saund decided to take up a new cause.

In meetings with Indian diaspora groups, a more contemporary congressional representative from California, Tom McClintock, noted: “In my experience, there are typically two types of political parties worldwide — those that are authoritarian and those that fight authoritarianism.” [21] Over a half-century earlier, the first Indian-American in U.S. Congress, expressed a similar sentiment after his own experiences witnessing the global political scene. “America has been given the leadership of the free way of life, based upon a democratic system of government that recognizes the dignity of man,” Saund wrote. “The other side is represented by international communism where a minority rules by force, where free thought is suppressed, and the individual is merely regarded as a tool of the state.” [22]

Consequently, Saund was convinced that the best path for the United States government to trod was to focus international relations on human rights issues. A biographer of Saund from the Riverside Historical Society describes the congressman as “almost prophetic in his views about channeling foreign aid through central governments.” He believed unconditional promises of cash “would lead to corruption.” [23]

Believing that aid to foreign governments should be conditional on their respect for human rights, he introduced a House resolution declaring: “It is the desire, hope, and expectation of the Congress that nations receiving military assistance under the mutual-security program guarantee to their people freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and freedom of the press.” [24]

Saund then proceeded to fight, tooth-and-nail, to introduce an amendment to the 1961 Foreign Assistance Act.

The Act completely reorganized the structure of the United States Government’s foreign aid system, unifying existing agencies and separating military from non-military aid. But one of the most extreme changes it proposed was to give the executive power to unilaterally grant foreign aid loans on a long-term basis to any country — in other words, allow the president to authorize multi-year loans of American tax dollars to foreign governments without having to receive annual approval from Congress in the form of an appropriations bill.

Saund found the proposal intolerable; as reported at the time by The Milwaukee Sentinel, he considered the Act “an attempt to avoid congressional control over the government’s purse.” [25]

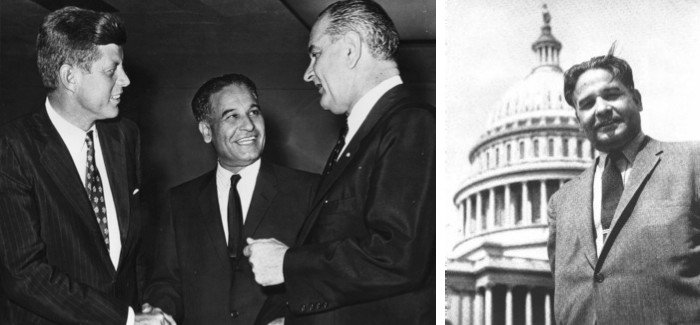

So, on August 16, 1961, Congressman Saund took to the floor of the House to defend his amendment. His stance set him directly at odds with President John F. Kennedy, who was specifically requesting the new power. Just six days earlier, the president had expanded U.S. involvement in Vietnam by ordering a surreptitious chemical defoliation program, spraying the Vietnamese jungles with poisons as an counterinsurgency measure. Eager to increase foreign aid to South Vietnam and other nations without having to secure support for his vision from the elected representatives of the people, Kennedy now demanded the Foreign Assistance Act.

Saund, however, would not let the Act pass so long as it granted the president such unprecedented and unrestrained new power.

Agreeing to provide aid to a foreign country for multiple years at a time, he cautioned, put the U.S. in the unfortunate position of committing to fund countries where “governments were overthrown and the character of officials completely changed.” [26] He offered an example:

“Suppose that the Congress had passed this kind of a bill 3 years ago. That was the time when Iraq was governed by a King and Prime Minister who were very friendly toward the United States. Suppose then we had promised the King of Iraq an annual sum of $100 million for 5 years…. One day we woke up to find that the King and Prime Minister were gone and the Government was taken over by a revolutionary leader not very friendly to the United States of America. Then, if we had decided later that it was not in the best interests of the United States to give this massive aid to the new government of Iraq, where would we be? We would be in a position of offering apologies and making excuses for not giving a foreign government our own money.” [27]

The better option, Saund proposed, was to pass his amendment to the Act to require yearly reauthorization by Congress of foreign aid packages.

When another representative opposed the Saund Amendment, expressing his surprise “at Saund’s opposition to long-term aid in view of the fact India had benefited by this kind of assistance,” Saund replied that he was now an American, not an Indian. Further, he said, “he made his judgments not on the basis of what was good for India but what was good for the United States.” [28]

In fact, Saund seemed suspicious of the very idea of foreign aid, suggesting that, although “the purpose of this program is to help the less fortunate people in the underdeveloped areas of the world,” those benefiting from the bailouts were “a thin strata on top.” [29]

“We have been identified with the ruling classes,” he warned. “We have been coddling kings and dictators and protecting the status quo. The status quo for the masses of people in many lands means hunger, pestilence, and ignorance. There are glaring instances where our aid has helped to make the rich richer and the poor poorer.” [30]

The Saund Amendment passed by a razor-thin margin — a vote of 197-185 — but along with it was introduced language to the Act prohibiting aid from going to “the government of any country which engages in a consistent pattern of gross violations of internationally recognized human rights, including torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, prolonged detention without charges, causing the disappearance of persons by the abduction and clandestine detention of those persons, or other flagrant denial of the right to life, liberty, and the security of person, unless such assistance will directly benefit the needy people in such country.” [31]

This language remains a legally binding principle for U.S. foreign relations.

Despite a lifetime of working for self-determination, helping to achieve the independence of India from the British Empire, agitating against discriminatory laws until he finally was able to obtain U.S. citizenship, breaking racial barriers in government, speaking for the civil rights of blacks, and, finally, standing up against the use of American foreign aid to prop up foreign dictators, Saund might yet still have done much more.

Yet tragically, in 1962, at the outset of his campaign for a fourth term in the House of Representatives, Saund suffered a stroke that left him unable to speak or even stand. With the help of his wife, Marian, he eventually recovered the ability to walk, but was compelled to withdraw from public life. He spent the rest of his years with his family in Southern California until his death on April 22, 1973.

Saund’s policies should serve as an inspiration to all who seek to follow in his footsteps. A judge, a writer, a civil rights activist, the man declared: “Discrimination of man against man in any form is repugnant to the ideals which all Americans cherish.” However, only two other Indian-Americans have subsequently been elected to U.S. Congress — Ami Bera and Bobby Jindal — and neither has stood as a particularly shining example of principle. Bera, on the one hand, was widely protested by Indian diaspora members for his denial of the 1984 Sikh Genocide and patronage of India’s genocide-linked Prime Minister, Narendra Modi [32]; Jindal, on the other hand, dealt with his cultural heritage by abandoning his birth-name, Piyush, and bloodthirstily asks: “How else do we win wars if not by killing our way to victory?” [33]

In contrast, Saund stated: “No people, no nation has ever won or ever can win real freedom through violence.” [34]

Thus, Dalip Singh Saund is rightly remembered as a statesman of supreme principle who recognized his duty to serve his own country first and foremost, raised a courageous voice for truth, reason, and liberty, and defended all minorities as he demanded recognition of equal rights.

Citations:

[1] Saund, Congressman Dalip Singh. U.S. House of Representatives. Speech. June 14, 1957.

[2] Interview with Senator Harry P. Cain. WCKT Miami. July 12, 1959. Click to view video.

[3] CA State Legislature. SCR 104. “Relative to the 100-year anniversary of the Sikh American community.” August 20, 2012

[4] Patterson, Tom. “Triumph and Tragedy of Dalip Saund.” California Historian. June 1992.

[5] CA State Legislature.

[6] Kaur, Anju. “Smithsonian alters Gadar history.” SikhNN.com. May 16, 2014.

[7] CA State Legislature.

[8] Singh, Roopinder. “Remembering the US Congressman from India.” The Tribune. January 12, 2002.

[9] Cain, Senator Harry P.

[10] Saund, Dalip Singh. My Mother India. Preface.

[11] Ibid. Chapter 4.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Singh, Roopinder.

[16] King, Jr., Dr. Martin Luther. The Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr. Warner Books. 1998. Chapter 11.

[17] Saund, Congressman Dalip Singh. June 14, 1957.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Saund, Dalip Singh. My Mother India. Chapter 8.

[20] Ibid.

[21] “USA: Bahujans and Christians Link Arms With Sikhs to Warn Congressman About Persecution in India.” Sikh Siyasat. May 13, 2015.

[22] Saund, Dalip Singh. My Mother India. Chapter 9.

[23] Patterson, Tom.

[24] Saund, Dalip Singh. My Mother India. Chapter 9.

[25] “Congress Cuts Alters JFK’s Aid Requests.” Milwaukee Sentinel. August 17, 1961.

[26] Speech of Hon. D.S. (Judge) Saund. Congressional Record. Proceedings and Debates of the 87th Congress, First Session. “Saund Amendments Sets Brakes on Foreign Aid Spending.” August 16, 1961.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Milwaukee Sentinel.

[29] Congresional Record. August 16, 1961

[30] Ibid.

[31] 22 U.S.C. § 2151n: US Code – Section 2151N: Human rights and development assistance.

[32] NRI minorities disavow Indian-American Congressman Ami Bera as he begins second term. Sikh Siyasat. January 6, 2015.

[33] Yuhas, Alan. “Governor Bobby Jindal talks foreign policy: ‘We are at war with radical Islam’.” The Guardian. March 16, 2015.

[34] Saund, Dalip Singh. My Mother India. Chapter 5.